STATE OF BEING – BEING AS A STATE

The philosophy of 20th century art and contemporary aesthetics is based on paradigmatic truth claims. This may be the reason why contemporary positions from the fields of aesthetic research are convinced that art “[…] should be grasped in its self-will, its autonomy” instead of subjecting it to a philosophically pre-determined complex of problems. “(Rebentisch, Juliane: Theorien der Gegenwartskunst zur Einführung. Hamburg 2013, p.42.).

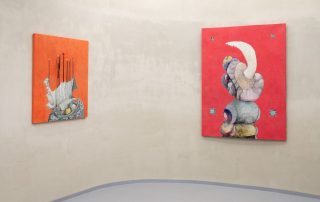

Within this matrix – the negation of a concrete “truth aesthetic” and / or a canonical reality – the works of Phillip Grechulevich must also be considered – especially because the contents cannot be taken directly from the images` motifs. The works in the exhibition rather show strongly oppositional attitudes and the merging of different pictorial strategies: the counteracting of the strictly symmetrical composition through an amorphous formal language, dualistic predicates such as monochrome space and surfaces filled with ornamental graphics, and a “perspective” and “motif” that move away from the picture, referring to the viewer´s perceptual phenomena.

In this way, the viewer finds himself in front of enigmatic pictorial landscapes, which, despite the exact, symmetrical composition, poetic resolution and amorphous imagery, do not form a concrete-narrative level and thus refer to the viewer’s horizon of perception and to his active involvement.

Grechulevich understands these processes as a “state of being”, whereas he describes his artistic practice as “being in this state”.

COSMIC SYMMETRY – AMORPHIC POETICS

A more precise description of Grechulevich’s pictorial strategies makes it possible to recognize concrete relationships – especially with regard to the merging of apparently oppositional attitudes: symmetrical pictorial axes, circular elements or elements set as points, which make a geometric division of the pictorial space. These are combined with amorphous structures or bodies formed by graphic lines, reminiscent of cell-like tissue. The artist describes these figures as “archetypes” of moods and conditions that people commonly experience in all kinds of situations.

For Grechulevich, his painting process represents an opportunity to consciously and specifically perceive and focus on these moods and states. However, his focus is not primarily on an emotional “experiencing” of these moods and states, but on reflexively locating, visualizing and imagining them in their entirety. This procedure enables the artist to visualize his personal moods and states in a kind of “universal image geometry”: the lines divide and connect spatial relationships – from the autonomy of the single body to the totality of the spatial image. The precise positioning and arrangement of the points and the circular bodies are reminiscent of mathematical spatial principles of inversion symmetry.

The rather flat amorphous figures seem to move in an unexplained relationship between a two-dimensional and a three-dimensional space. Here, the promise inherent in point symmetry that a figure is to be regarded as point-symmetrical if it depicts itself through reflection at a point of symmetry is not kept: the question of what is reflected and what can be experienced in terms of dimensions ultimately refers to the viewer and their highly personal handling of their own “moods and conditions”.

CONOGRAPHY – CHOROLOGY

A central point of Grechulevich’s pictorial strategies is his handling of the pictorial space: the background is widely covered by a monochrome design of curves,

organically-free and interwoven lines. The motif is often centered in this composition, placed in the foreground and often covered with a graphic line structure similar to that in the background. The often monochrome background, the graphic lines placed on it and the centered motif in the foreground create a pictorial space that continuously alternates between flat, deep planes and a geometric depth as well as an immediate presence of the foreground motif and the spatial division executed in the background. The simultaneity of the depicted levels and perspectives, the frontal and axial figures in the foreground and the – at first glance – flat background form an interpictorial reference to icon painting: This forms a firmly anchored subject in the collective and cultural image memory of Georgia – which is for the painter a decisive criterion for dealing with this visual language.

Icon painting follows a canonical structure – both within the composition and with regard to the content of the presentation. George Kordis sums up some of the major stylistics of icon painting: a lack of a creative depth, a static formation of the surface, the color semantics in the design and the structuring by lines, the plasticity of form and also the striving for rhythm. (Kordis, George: Icon as Communion, Brookline MA 2010, pp. 51-58). Light, space and perspective are discussed as further design elements, as noted by Roland Betancourt, for example, who states that the golden background is not only a symbol for the omnipresence of divine reality, but also “air” around the depicted figure, furthermore it is a medium of human vision marking a distance between worldly possibilities (“potentiality”) and divine omnipresence (“actuality”). (Betancourt, Roland: The Icon’s Gold: A Medium of Light, Air, and Space, in: West 86th, 23.2 (2016) p. 252, p. 264) The frontal representation and labeling to classify the presented topic, an orderly categorization system and a conscious presence and absence are further principles of icon painting. (Maguire, Henry: The Icons of Their Bodies. Saints and Their Images in Byzantium, Princeton NJ 1996, pp 313-314 / Németh, Thomas Mark: Icons. Basics, approaches, inquiries, in: Dominican Magazine for Faith and Society, issue 3, July-September, 2019, pp. 122-124). The principles of icon painting listed here are reflected in Grechulevich’s work like an abstract, freely varying corpus. The image strategies are adopted like a subtle intertext, but the content and the objectives differ. Grechulevich thus combines the creative means, using them for a multi-layered self-interpretation and linking them reflexively to re-enact their own content. The result is not only a deconstruction of the canonical principles and the religiously shaped symbolism of icon painting, but also a reflection on the cultural canon as the legacy and charisma of these images, in the collective visual memory of Georgian society.

Meanwhile, Grechulevich’s method is also to be understood as a spatiotemporal chorology that goes beyond historical space, via the paths of painterly abstraction, the reflection of his socialization images and collective memory, without striving for a “truth aesthetic” or any kind of concrete and expedient narrative, leading to his very own personal visual identity.